| Apple fruit | |

|---|---|

of the Honeycrisp cultivar | |

| |

| Flowers | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Rosaceae |

| Genus: | Malus |

| Species: | M. domestica |

| Binomial name | |

| Malus domestica Borkh., 1803 | |

| Synonyms[1][2] | |

| |

Apple

Apple trees are large if grown from seed. Generally, apple cultivars are propagated by grafting onto rootstocks, which control the size of the resulting tree. There are more than 7,500 known cultivars of apples, resulting in a range of desired characteristics. Different cultivars are bred for various tastes and use, including cooking, eating raw and cider production. Trees and fruit are prone to a number of fungal, bacterial and pest problems, which can be controlled by a number of organic and non-organic means. In 2010, the fruit's genome was sequenced as part of research on disease control and selective breeding in apple production.

Apple

| Apple | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fruit of the Honeycrisp cultivar | |

| |

| Flowers | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Rosaceae |

| Genus: | Malus |

| Species: | M. domestica |

| Binomial name | |

| Malus domestica Borkh., 1803 | |

| Synonyms[1][2] | |

| |

An apple is an edible fruit produced by an apple tree (Malus domestica). Apple trees are cultivated worldwide and are the most widely grown species in the genus Malus. The tree originated in Central Asia, where its wild ancestor, Malus sieversii, is still found today. Apples have been grown for thousands of years in Asia and Europe and were brought to North America by European colonists. Apples have religious and mythological significance in many cultures, including Norse, Greek, and European Christian tradition.

Apple trees are large if grown from seed. Generally, apple cultivars are propagated by grafting onto rootstocks, which control the size of the resulting tree. There are more than 7,500 known cultivars of apples, resulting in a range of desired characteristics. Different cultivars are bred for various tastes and use, including cooking, eating raw and cider production. Trees and fruit are prone to a number of fungal, bacterial and pest problems, which can be controlled by a number of organic and non-organic means. In 2010, the fruit's genome was sequenced as part of research on disease control and selective breeding in apple production.

Worldwide production of apples in 2018 was 86 million tonnes, with China accounting for nearly half of the total.[3]

Contents

Etymology

The word apple, formerly spelled æppel in Old English, is derived from the Proto-Germanic root *ap(a)laz, which could also mean fruit in general. This is ultimately derived from Proto-Indo-European *ab(e)l-, but the precise original meaning and the relationship between both words[clarification needed] is uncertain.

As late as the 17th century, the word also functioned as a generic term for all fruit other than berries but including nuts—such as the 14th century Middle English word appel of paradis, meaning a banana.[4] This use is analogous to the French language use of pomme.

Description

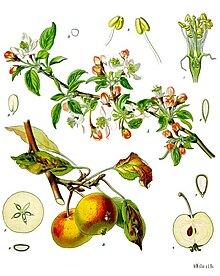

The apple is a deciduous tree, generally standing 2 to 4.5 m (6 to 15 ft) tall in cultivation and up to 9 m (30 ft) in the wild. When cultivated, the size, shape and branch density are determined by rootstock selection and trimming method. The leaves are alternately arranged dark green-colored simple ovals with serrated margins and slightly downy undersides.[5]

Blossoms are produced in spring simultaneously with the budding of the leaves and are produced on spurs and some long shoots. The 3 to 4 cm (1 to 1 1⁄2 in) flowers are white with a pink tinge that gradually fades, five petaled, with an inflorescenceconsisting of a cyme with 4–6 flowers. The central flower of the inflorescence is called the "king bloom"; it opens first and can develop a larger fruit.[5][6]

The fruit matures in late summer or autumn, and cultivars exist in a wide range of sizes. Commercial growers aim to produce an apple that is 7 to 8.5 cm (2 3⁄4 to 3 1⁄4 in) in diameter, due to market preference. Some consumers, especially those in Japan, prefer a larger apple, while apples below 5.5 cm (2 1⁄4 in) are generally used for making juice and have little fresh market value. The skin of ripe apples is generally red, yellow, green, pink, or russetted, though many bi- or tri-colored cultivars may be found.[7] The skin may also be wholly or partly russeted i.e. rough and brown. The skin is covered in a protective layer of epicuticular wax.[8] The exocarp (flesh) is generally pale yellowish-white,[7] though pink or yellow exocarps also occur.

Wild ancestors

The original wild ancestor of Malus domestica was Malus sieversii, found growing wild in the mountains of Central Asia in southern Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and northwestern China.[5][9] Cultivation of the species, most likely beginning on the forested flanks of the Tian Shan mountains, progressed over a long period of time and permitted secondary introgression of genes from other species into the open-pollinated seeds. Significant exchange with Malus sylvestris, the crabapple, resulted in current populations of apples being more related to crabapples than to the more morphologically similar progenitor Malus sieversii. In strains without recent admixture the contribution of the latter predominates.[10][11][12]

Genome

Apple is diploid, though triploid cultivars are not uncommon, has 17 chromosomes and an estimated genome size of approximately 650 Mb. Several whole genome sequences has been made available, the first one in 2010 was based on the diploid cultivar ‘Golden Delicious’.[13] However, this first whole genome sequence turned out to contain several errors[14] in part owing to the high degree of heterozygosity in diploid apple which, in combination with an ancient genome duplication, complicated the assembly. Recently, double- and trihaploid individuals have been sequenced, yielding whole genome sequences of higher quality.[15][16] The first whole genome assembly was estimated to contain around 57,000 genes,[17] though the more recent genome sequences support more moderate estimates between 42,000 and 44,700 protein coding genes.[18][19] Among other things, the availability of whole genome sequences has provided evidence that the wild ancestor of the cultivated apple most likely is Malus sieversii. Re-sequencing of multiple accessions has support this, while also suggesting extensive introgression from Malus sieversii following domestication.[20]

History

| |

Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Malus sieversii is recognized as a major progenitor species to the cultivated apple, and is morphologically similar. Due to the genetic variability in Central Asia, this region is generally considered the center of origin for apples.[21] The apple is thought to have been domesticated 4000–10000 years ago in the Tian Shan mountains, and then to have travelled along the Silk Road to Europe, with hybridization and introgression of wild crabapples from Siberia (M. baccata), the Caucasus (M. orientalis), and Europe (M. sylvestris). Only the M. sieversii trees growing on the western side of the Tian Shan mountains contributed genetically to the domesticated apple, not the isolated population on the eastern side.[22]

Chinese soft apples, such as M. asiatica and M. prunifolia, have been cultivated as dessert apples for more than 2000 years in China. These are thought to be hybrids between M. baccata and M. sieversii in Kazakhstan.[22]

Among the traits selected for by human growers are size, fruit acidity, color, firmness, and soluble sugar. Unusually for domesticated fruits, the wild M. sieversii origin is only slightly smaller than the modern domesticated apple.[22]

At the Sammardenchia-Cueis site near Udine in Northeastern Italy, seeds from some form of apples have been found in material carbon dated to around 4000 BCE.[23] Genetic analysis has not yet been successfully used to determine whether such ancient apples were wild Malus sylvestris or Malus domesticus containing Malus sieversii ancestry.[24] It is generally also hard to distinguish in the archeological record between foraged wild apples and apple plantations.

There is indirect evidence of apple cultivation in the third millennium BCE in the Middle East. There was substantial apple production in the European classical antiquity, and grafting was certainly known then.[24] Grafting is an essential part of modern domesticated apple production, to be able to propagate the best cultivars; it is unclear when apple tree grafting was invented.[24]

Winter apples, picked in late autumn and stored just above freezing, have been an important food in Asia and Europe for millennia.[25] Of the many Old World plants that the Spanish introduced to Chiloé Archipelago in the 16th century, apple trees became particularly well adapted.[26] Apples were introduced to North America by colonists in the 17th century,[5] and the first apple orchard on the North American continent was planted in Boston by Reverend William Blaxton in 1625.[27] The only apples native to North America are crab apples, which were once called "common apples".[28] Apple cultivars brought as seed from Europe were spread along Native American trade routes, as well as being cultivated on colonial farms. An 1845 United States apples nursery catalogue sold 350 of the "best" cultivars, showing the proliferation of new North American cultivars by the early 19th century.[28] In the 20th century, irrigation projects in Eastern Washington began and allowed the development of the multibillion-dollar fruit industry, of which the apple is the leading product.[5]

Until the 20th century, farmers stored apples in frostproof cellars during the winter for their own use or for sale. Improved transportation of fresh apples by train and road replaced the necessity for storage.[29][30] Controlled atmosphere facilities are used to keep apples fresh year-round. Controlled atmosphere facilities use high humidity, low oxygen, and controlled carbon dioxide levels to maintain fruit freshness. They were first used in the United States in the 1960s.[31]

Significance in European cultures and societies

Germanic paganism

In Norse mythology, the goddess Iðunn is portrayed in the Prose Edda (written in the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson) as providing apples to the gods that give them eternal youthfulness. The English scholar H. R. Ellis Davidson links apples to religious practices in Germanic paganism, from which Norse paganism developed. She points out that buckets of apples were found in the Oseberg ship burial site in Norway, that fruit and nuts (Iðunn having been described as being transformed into a nut in Skáldskaparmál) have been found in the early graves of the Germanic peoples in England and elsewhere on the continent of Europe, which may have had a symbolic meaning, and that nuts are still a recognized symbol of fertility in southwest England.[32]

Davidson notes a connection between apples and the Vanir, a tribe of gods associated with fertility in Norse mythology, citing an instance of eleven "golden apples" being given to woo the beautiful Gerðr by Skírnir, who was acting as messenger for the major Vanir god Freyr in stanzas 19 and 20 of Skírnismál. Davidson also notes a further connection between fertility and apples in Norse mythology in chapter 2 of the Völsunga saga: when the major goddess Frigg sends King Rerir an apple after he prays to Odin for a child, Frigg's messenger (in the guise of a crow) drops the apple in his lap as he sits atop a mound.[33] Rerir's wife's consumption of the apple results in a six-year pregnancy and the birth (by Caesarean section) of their son—the hero Völsung.[34]

Further, Davidson points out the "strange" phrase "Apples of Hel" used in an 11th-century poem by the skald Thorbiorn Brúnarson. She states this may imply that the apple was thought of by Brúnarson as the food of the dead. Further, Davidson notes that the potentially Germanic goddess Nehalennia is sometimes depicted with apples and that parallels exist in early Irish stories. Davidson asserts that while cultivation of the apple in Northern Europe extends back to at least the time of the Roman Empire and came to Europe from the Near East, the native varieties of apple trees growing in Northern Europe are small and bitter. Davidson concludes that in the figure of Iðunn "we must have a dim reflection of an old symbol: that of the guardian goddess of the life-giving fruit of the other world."[32]